During the past 10 years, the Los Angeles River has moved from object of dumpster humor to a symbol of urban rewilding. According to the city’s LARiverWorks, there are nine projects worth $500 million in the pipeline, from funded design stage to construction. Although two fish passages are envisioned, one in downtown Los Angeles, the Lower LA River Channel Restoration and Access stands out for conservationists.

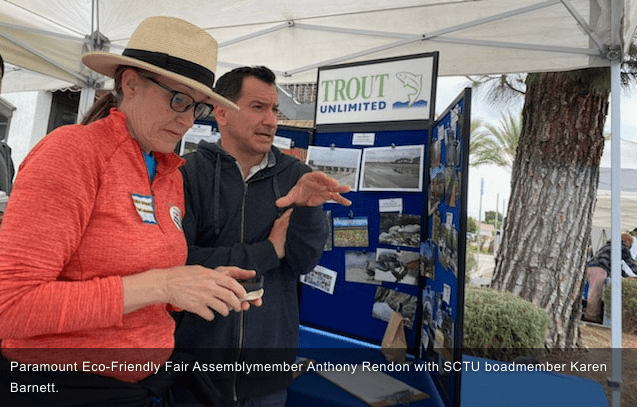

“The LA River restoration effort is not about fishing, and it’s not really about trout,” said Bob Blankenship, of TU’s South Coast Chapter, who along with another TU board member, Karen Barnett, spearheaded the effort. “It’s about helping local people reimagine their local river, with global exposure that will jump start other restoration efforts.”

According to the LA Master Plan, many histories of the LA River focus on two central narratives: the devastating floods of the 1930s, and the rapid development in the first half of the 20th century that led the United States Army Corps of Engineers and the LA County Flood Control District to channelize and line LA’s main inland waterway. Now, designers, engineers and conservationists are reimagining how 51 miles of mostly concrete that cuts through neighborhoods, many of them underserved, can be knitted back together.

The idea of “urban rewilding” is one that has gained traction in other major cities, both in America as well as Europe. The Associated Press reported

Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium and the nonprofit Urban Rivers are installing “floating wetlands” on part of the Chicago River to provide fish breeding areas, bird and pollinator habitat and root systems that cleanse polluted water. Or the Rewild London Fund that plans to spend more than $850,000 dedicated to increasing, for example, water voles in freshly restored waterways, as well as helping swifts and sparrows to again flourish in the city.

Back in Los Angeles, working with grant money of $300,000, the South Coast Chapter’s project team, as well as the City of Paramount, and the Odyssey STEM Academy, completed a conceptual design for the Lower LA River that incorporates seasonal public access and open space in a naturalized river channel.

David Johnson, Community Services Manager for the City of Paramount, put it well.

“Paramount residents live in a highly urbanized, built-out environment. A reconstructed natural river segment here would provide an amazing opportunity to connect with the natural environment in our own backyard,” he said. “It is important for residents to look upon the Los Angeles River as something that is functioning and crucial to protect, particularly for any impacts downstream where it flows to our local beaches and ocean.

Trout Unlimited basically turned the design element on its head, by involving local residents — most notably students from the Odyssey Stem Academy — then from that input, nudging the design professionals to technically stretch to meet the neighborhood’s criteria. A prime concern is in any river reimagining is the possibility of a 100-year flood event. In the case of the lower river project, that means a fish passage that allows returning steelhead to rest and regenerate in its pools and shade, also must be able to move enough water through the channel to avoid flooding.

Nicole Bottomley teaches in the STEM (science, technology, engineers and mathematics) curriculum at Odyssey Stem Academy, a public school in the Paramount Unified School District. Senior capstone projects were interdisciplinary, which included advisers in math, English, science and Spanish.

“I am so grateful for this organization to have given this to our community and these scholars,” Bottomley said.

Gerardo Silva, was graduated last year and is currently studying biology at Cerritos Community College with the hope of transferring to UCLA. He and his partner choose biodiversity and its effects on aerosols as their seamster-long project. To compare how rewinding a place contributes to healthier air, they chose to compare Glendale Narrows, an area of the river north of Paramount, that still has a soft bottom section, with the area around Dills Park and a housing development unique to Paramount called the “Sans” neighborhood, because each street is named for a saint and begins with the word “San.”

The riparian area of the Narrows is home to dozens of bird species, including snowy egrets, great blue herons and migrating Canadian geese. They are drawn to the flowing water, as well as to the native plants here that include native Arroyo willows and water cress. It’s also one of the best places to imagine what the migration of the endangered Southern California steelhead was like, when thousands of these fish returned to the San Gabriel Mountains several dozen miles away to spawn.

“The majority of our project was tons and tons of research to back up our hypothesis and claims,” Silva said.

Although Silva intimately was unable to prove his hypothesis because of lack of time, when you speak with him you get the feeling this project will help propel him into a science career. And one day he may see the Lower River Channel Restoration realized, along with an urban community’s dream of a greener future.

See you on the river, Jim Burns

This piece originally ran in TROUT magazine, summer 2023